If we look through tennis lore, writing and commentary abound regarding Novak Djokovic’s famed mental toughness. Regardless of what you think about Djokovic, even the most ardent hater begrudgingly admits that, “Yes, okay, I don’t really like the guy… but I have to admit that he’s mentally tough.”

But here’s my argument: in the sporting culture, what most people call “mental toughness*” is actually the skill of accepting and letting go of immense frustrations and negative emotions, and then redirecting attention under pressure. And Djokovic is the best example of this on the ATP Tour.

My experience in the tennis and sporting world is that “mental toughness” is thrown around carelessly. It’s poorly defined by the general sporting population, and because of a simplistic or incorrect misunderstanding of what it entails, there’s lots of confusion in the general tennis and athletic culture regarding what it is exactly.

Tennis players beat themselves up for not being mentally tough enough. “You piece of shit! Why aren’t you more mentally tough? Like Djokovic is!”

Coaches and parents yell platitudes at players about being tougher and “fighting more” and showing more, “heart.”

But what does that all mean?

How is a player supposed to implement that?

I’ve written before about how Djokovic uses mindful-acceptance (or 3rd-wave) methods for self-regulation and also controlling his attention. (Attention, by the way, is your most valuable resource on the tennis court.) Though you may understand that he uses this approach, the larger query might be: how do I actually use these techniques myself?

It’s a common question in the athletes I speak to… so today I’m going to break it down for you. And I’m also going to show you something which will hopefully solidify this idea.

Back to this idea of attention being your most important resource. How do we build attention? Well… we have to practice.

From the Horse’s Mouth

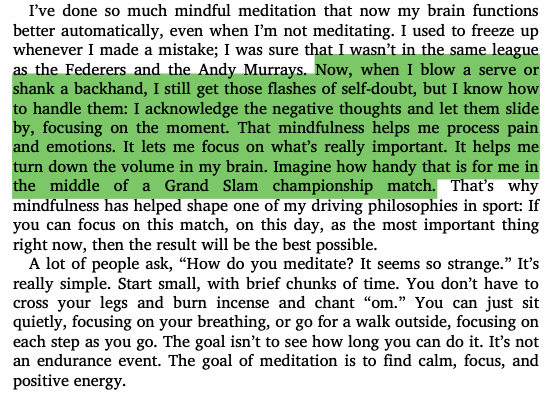

I want to share with you here an excerpt from Djokovic’s 2013 book, Serve to Win. I know it’s quite a block of text, but I implore you to read it because I think it will illuminate some ideas for you. Djokovic explains mindfulness in a way I wish every athlete could read; simple, practical, and completely free from the spiritual clichés that confuse so many people.

Hopefully a few concepts are clicking for you, but the first I want to start with is acceptance and non-judgment. I think, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts, that when it comes to the sporting world, there is a lot of macho-ness still out there.

Athletes want to feel, “mentally tough.” They want to feel, “Invincible,” and “unbreakable.” That problem is, unless you’re somewhat sociopathic or riding the highest high of your life, more than likely you’re going to struggle to feel this way consistently. More than likely, you’ll have doubts. You’ll have worries. You’ll have concerns.

And often, when we have these fears, we can amplify them further by not wanting to experience them.

“Why am I feeling this way?”

“I don’t want to be nervous.”

“I want to feel brave.”

“I want to feel ready to compete.”

Note how Djokovic writes about letting these thoughts come and go. Why does this strategy work? Because it reduces the secondary struggle of "not wanting to feel this way.” It stops the spiraling by reducing your negative reactions to your experience.

In fact, in one of the mindfulness tangential classes that I teach, the biggest misconception that I have to address with mindfulness is that it’s not about “clearing your mind,” “emptying your mind” or “finding peace and relaxation.” Rather, it’s about nonjudgemental awareness of our internal and external landscapes. And that also means an acceptance of the constant barrage of negative or critical thoughts that we might face during competition.

There’s a famous interview which I’ve covered in the past where Djokovic says—and here I’m paraphrasing—that it’s not normal to expect yourself to feel invincible in the toughest moments. You’re a human being. It’s only that he’s found a way to spend less time in those thoughts and emotions and feelings… and he’s able to redirect his attention more quickly to task-relevant thoughts.

Let me ask you this:

When it’s 3–4 30–40 in the 3rd set and you’re serving to not get broken, what do you want to be occupying your mind? Thoughts and concerns about potentially going down a break, losing, the effects of that loss on your social reputation or ranking? Or do you want to direct your attention toward task-relevant cues and ideas… following your routines, regulating your anxiety, planning out your serve and placing your following shot into the open court so that you can force an error? I think the answer is obvious to you.

That difference—between future-oriented worries and present-oriented focus—is the difference between a poor performance and a quality showing.

Don’t believe me? That’s fine. I just research mindfulness-based interventions in professionals tennis players. But you don’t have to take my word for it. Take Djokovic’s:

Note how Djokovic doesn’t embody the traditional, macho-man idea of mental toughness, where an athlete will never face mental challenges, negative thoughts, worries, and concerns. Rather, through his mindfulness practice, he understands that negative thoughts and self-doubt are a normal function of being a human being. He writes, “That’s why mindfulness has helped shape one of my driving philosophies in sport: If you can focus on this match, on this day, as the most important thing right now, then the result will be the best possible.” Put another way, Djokovic is able to modulate his relationship to his fears and anxiety and turn his attention back towards what matters most in the moment. In other words, he works every day to train his attentional control.

So once again I ask you… how do you train your attention?

Could You Get Stronger Without Resistance Training?

Here, now, we get to the crux of the matter. I once spoke with a high-level junior player whose parents informed me that she had been working with a mental coach for about 10 sessions or more. This coach, had simply been telling her to be, “present.”

“Be more present.”

“Be more present.”

But that’s like telling someone “be strong” without getting them to do any resistance training.

Would your bench press improve if you didn’t train?

What about your squat? If you didn’t load up that bar would you be able to move more weight?

What about pull-ups?

I think you get the idea; if you wouldn’t be able to improve your physical strength without training, why would your attentional control skills improve without practice?

Again, from Djokovic, “I do this every day for about 15 minutes, and it is as important to me as my physical training.” Here’s another way of thinking about it: you have to practice consistently to improve your mental skills. In this case, attentional control.

Just like your strength doesn’t grow without progressive overload, your attentional (and mental skills) won’t grow without deliberate and consistent practice. Hoping that when the rubber hits the road that you’ll be “more present” is not a mental training plan.

Your Takeaway

Mental toughness is not an ingrained personality trait. It’s actually a trainable skill. Djokovic isn’t “fearless” in the traditional, macho-man sense of mental toughness. He’s just trained his attentional control skills so deeply that he doesn’t let fear, frustration, and self-doubt control his behaviors. If you can learn to notice your thoughts, change your relationship with them, and bring your attention back to your task, you will play steadier, recover faster from hiccups, and compete closer and closer to your true potential.

Was This Week's Issue Helpful?

*Mental toughness is a distinct concept in the sport and performance psychology literature. There is healthy debate and discussion about how it is defined. In this this piece, when I refer to it, I’m referring to sporting culture definition of mental toughness—not the sport and performance psychology construct.

Disclaimer: I am not a licensed psychologist, mental health counselor, PsyD, or clinical PhD. I am currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology and am a sport psychology practitioner-in-training, working toward the Certified Mental Performance Consultant® (CMPC®) credential provided by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP). My work focuses on applied, non-clinical mental performance consulting, using evidence-based techniques grounded in psychology, sport science, and applied sport psychology to help athletes enhance focus, manage pressure, build confidence, and improve performance. I do not provide mental health counseling or clinical therapy. When needed, I will always refer clients to licensed mental health professionals for concerns beyond the scope of performance consulting. I have over 20 years of experience in tennis, including as a player, collegiate and professional coach, and director of programs. I am certified by the Professional Tennis Registry and am a member of Tennis Australia. My goal is to bring athletes the best research-backed insights to support long-term development and performance. If you are a researcher or practitioner and feel I’ve misunderstood or misrepresented any concept, I welcome you to reach out, and I will gladly review and issue corrections if appropriate.