Crowds rarely offer wisdom.

But yesterday was different.

I was watching the French Open final in a large, social space yesterday with lots of players and fans, and someone said, “It’s all mental. They’re all so good. It’s all mental.”

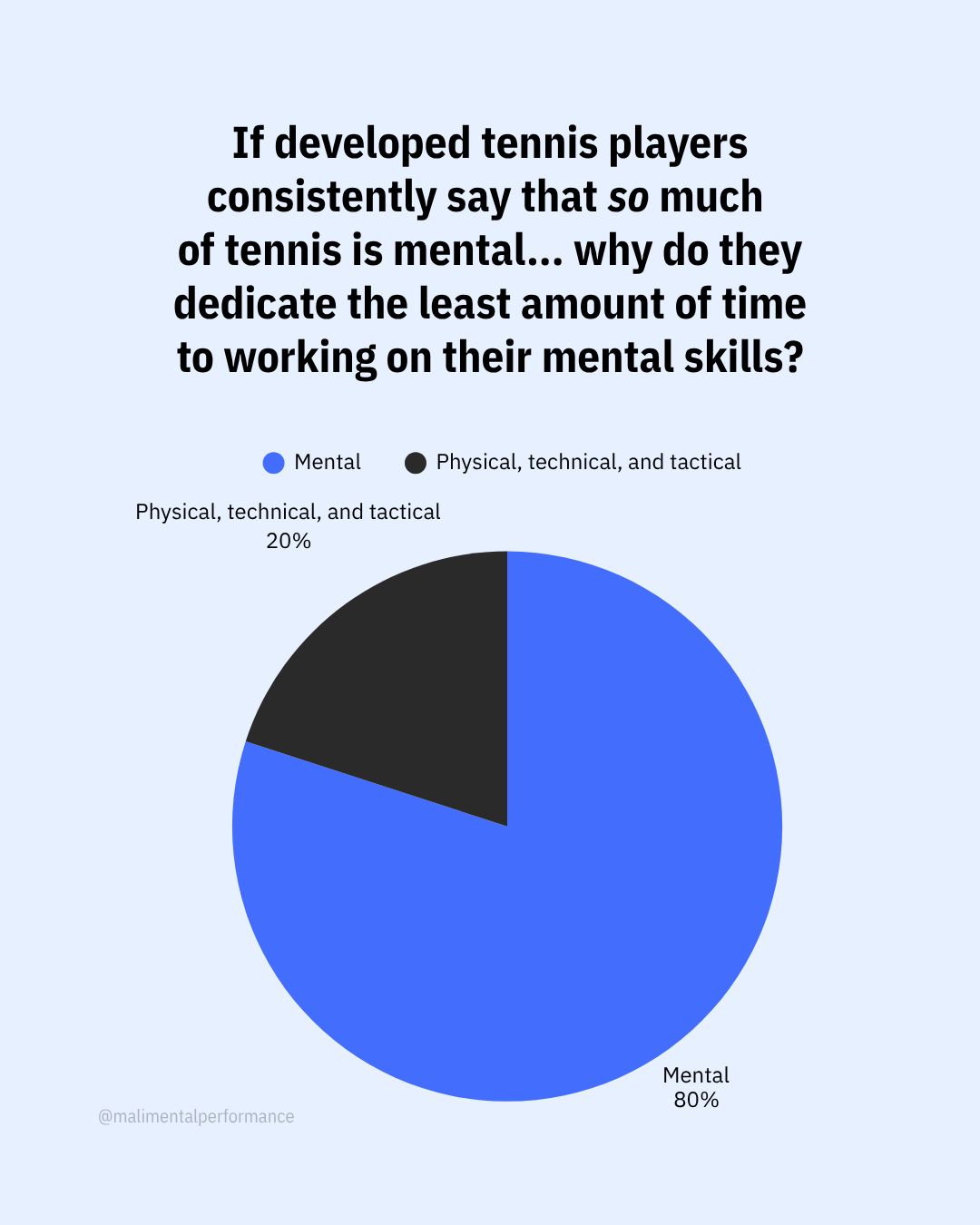

That line is almost a mantra in the tennis world: If you speak to recreational, collegiate, professional, and even developing junior players, they will begrudgingly acknowledge how much of this sport is based upon what happens within those 6 inches between your ears.

Regardless of level, players say things like, “Tennis is at least 80 percent mental.” Yes, we can’t overlook ball-striking, tracking skills, physical conditioning, and tactics, but a huge slice of the success pie is psychological. As Novak Djokovic put it, “Tennis is a mental game. Everyone is fit; everyone hits great forehands and backhands.”

If we all accept that, this begs the question: why are mental skills so often ignored? I went through a full junior career, time at an internationally renowned academy, college tennis (albeit at a small school), work as a collegiate coach, and years as a teaching pro before I haphazardly stumbled upon sport psychology. Others get that exposure earlier, sure, but the broader pattern remains in tennis—everyone talks about the mental game, but few actually train it. Why is that?

Kaufman et al. (2018) list three reasons for this very question:

#1: “I don’t have the time.”

To say there is disinformation and misunderstanding in this space is a major understatement. Among these confusions is the idea that one needs to commit hours of time a day to get the benefits of mental skills training.

I can see why one might think this way, though. For example, one might intuitively understand that playing tennis just once a week or going to the gym just once a week isn’t going to be that impactful. So perhaps the calculus goes something like this: “To start becoming mentally tough, I’m going to have to spend an hour a day working on my mindset or doing the mental work… and I don’t know how or how I will even have enough time to do that.”

While understandable, this view is completely wrong. An athlete can benefit from mental skills training in as little as 12 minutes a day (Jha, 2017)—this is if we’re going to take the Mindful Sport Performance Enhancement route (Kaufman et al., 2018). But, that’s the amazing thing about sport psychology! This field is so varied and diverse and there are many evidence-based interventions that have proven to be effective.

A player can also benefit from simpler skills such as pre-match goal-setting (to do so, though, one has to understand the different goal-types and the impacts that they have), arousal control, imagery, and confidence-building.

These do not take hours to learn or practice. In less than 10 minutes a day, you can benefit from these skills.

#2: “I don’t know where to start.“

This one I commiserate with. When I needed help, I didn’t know where to start. So I did what a normal person at that time would do. I googled. And I found the Wild Wild West. My results were populated by random “mental coaches” who didn’t have the appropriate sport science education, psychology education, nor the education on ethics, let alone time under a supervised practitioner.

What is worse is that players seeking help are often vulnerable in some regard, as I was. So, please take my word when I do say that I understand.

With all of this being said, I’ll tell you where you we do start: usually with a detailed intake session. You might think that an intake is a waste of time, but it’s the most valuable session that you will ever do with a mental performance consultant or a sport psychologist. It is their time to truly understand you—not just as an athlete, but also as a person in general. Based on what is discussed in the intake, the practitioner will make an educational plan to help you improve and apply skills from sport psychology.

If you don’t want to work with someone and want to have a crack at it yourself, I recommend educating yourself on goal-setting and assessing your goal orientation. I send a PDF summarizing goal-setting when you join my newsletter. Send me an email if you can’t locate yours.

'Hang on,’ you might think. ‘Why is this guy helping me for free?’

Well, I figure that there is enough misinformation out there that sharing some “quality” information can’t but help. Maybe you’ll find it useful and consider my help eventually, or send a referral my way in time. The philosophy is to share lots of goodwill and information, and hopefully it will be returned in some way or another!

#3: Fear of the unknown

Which leads us to the last point that Kaufman et al. cover. A fear of the unknown.

People have really strange ideas about working with sport psychology professionals. Remember, though, that applied sport pyschology is not clinical, meaning that we only focus on performance enhancement and are trained to refer out if we detect signs of generalized anxiety, depression, etc.

Ideas like:

“Is this guy going to uncover childhood traumas?”

“Am I going to be prescribed medicine?”

“To work with someone to improve my mental performance skills must mean that I am deficient in some way and that I must have some real problems.”

“Champions don’t need help with mental performance.”

All of the above are not only patently untrue but are demonstrably false.

For example, practitioners in applied sport psychology might ask about general team or family dynamics and how they impact your performance, but we are not going to start digging around regarding childhood schemas that impact your daily functioning. We are trained to strictly operate in the performance domain. And, no, we do not have prescriptive powers.

The idea that athletes who work with someone are deficient in some ways is perhaps the most harmful. If I’m being honest, it is mostly propagated by macho men who have no idea what applied sport psychology is and how we try to help athletes. They have some strange conception in their head and run off it. Sorry if I’ve offended you, macho man, if you’re reading this. Mental performance is the application of evidence-based sport psychology to help athletes improve performance, manage anxiety, improve concentration, etc. Almost everyone can benefit from that if they want to improve how they perform.

Don’t believe me?

Speak to these players who have all been confirmed to have worked with someone in the sport psychology/mental performance space:

Roger Federer (when younger and still in his hot-headed phase)

Carlos Alcaraz

Iga Swiatek

Andy Murray

Madison Keys

Ivan Lendl

Aryna Sabalenka

Dominika Cibulkova

Carla Suarez Navarro

Petra Kvitova

Stefanos Tsitsipas

Denis Shapovalov

I hope this has helped clarify any of the confusion you may have had about this space. I will once again draw the conversation to where we began. If we agree that so much of tennis is mental, why do we spend so little time working on our mental skills?

Disclaimer: I am not a licensed psychologist, mental health counselor, PsyD, or clinical PhD. I am currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology and am a sport psychology practitioner-in-training, working toward the Certified Mental Performance Consultant® (CMPC®) credential provided by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP). My work focuses on applied, non-clinical mental performance consulting, using evidence-based techniques grounded in psychology, sport science, and applied sport psychology to help athletes enhance focus, manage pressure, build confidence, and improve performance. I do not provide mental health counseling or clinical therapy. When needed, I will always refer clients to licensed mental health professionals for concerns beyond the scope of performance consulting. I have over 20 years of experience in tennis, including as a player, collegiate and professional coach, and director of programs. I am certified by the Professional Tennis Registry and am a member of Tennis Australia. My goal is to bring athletes the best research-backed insights to support long-term development and performance. If you are a researcher or practitioner and feel I’ve misunderstood or misrepresented any concept, I welcome you to reach out, and I will gladly review and issue corrections if appropriate.