“We suffer more in imagination than in reality.” — Seneca

I talk to many players seeking mental performance and applied sport psychology help and one of the most common themes that comes up is a fixation on what will happen if they lose a match or don’t perform to their expectations.

What if I lose first round?

What if I can’t defend my ranking points from last year?

What if I don’t get into my dream college?

What if I lose to my friend Janet?

The first thing that I like to tell these players is that they are not alone. There should be some weight given to the fact that tennis players and other athletes, regardless of who they are, all suffer from thoughts like this. You share a common humanity with others (borrowing a concept from Kristin Neff), and I hope you don’t feel like you’re the only person who’s experiencing these thoughts.

Now, most mental performance standards might encourage competitors experiencing these negative thoughts to reframe them in a positive or affirmative.

Hey, have you tried reframing your negative thoughts?

What if I don’t lose first round?

What if I can defend my ranking points?

What if I don’t lose to my friend Janet?

To be frank, I find the “let’s reframe your thought to be something positive,” as quite a surface-level intervention. It’s almost like a platitude that’s doled out whenever someone professes to experience something negative.

Additionally, correct me if I’m wrong, but to a client experiencing this attempt at reframing, the effort can seem almost comical.

Is this guy serious? Is he really telling me to change my negative thoughts to positive ones? Doesn’t he think that I’ve already tried this? Why the hell am I paying this guy?

So what’s the alternative? And what do I find to be personally more useful?

Catastrophizing and Fear of Consequences

What I’ve come to realize through my work with athletes and research is that most of these “what if” thoughts are not really about the event itself.

They’re about the consequences that the player imagines will happen—and, more importantly, how they perceive what those consequences say about them.

Instead of a loss in the first round just meaning that you didn’t perform well that day, it turns into: “Losing in the first round means that my tennis career is doomed.” Or worse, “Maybe I’m just not good enough to keep playing at this level. Maybe it’s time to hang up the rackets.”

Not defending ranking points doesn’t just hurt your ranking; it means that last year was a fluke and you’ll never reach that level again.

The technical term for this kind of thinking in cognitive therapy is catastrophizing: taking a potential negative outcome and inflating it up until it feels like a threat to your entire identity, personhood, or your future.

Athletes who tend to catastrophize get stuck in patterns and spirals of what-if thinking.

This is where Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), or Cognitive Behavioral Training, for our non-clinical purposes, offers a more powerful intervention—not to replace the thought, but to first accept that it exists and then investigate and confront it. And one of the most effective tools for that is decatastrophizing.

So What If? (Decatastrophizing)

When players are stuck in cycles of thought like this—what if x? What if y? What if z?—the remedy is often to bring up the question, “So what if?”

For example, if a player is so entirely fixated on winning matches that each match becomes a life-or-death occurrence, we might broach the topic by saying, “So what if you lose? What will happen? What will that look like? And what will happen after that?”

I should add here that to use this technique, there needs to be a bit of rapport between the practitioner and the athlete, and that the competitor needs to be in a state of change to accept this thought experiment. Additionally, the athlete needs to feel safe discussing this with the practitioner and more importantly they need to be ready to confront whatever it is that might be causing them anxiety.

Oftentimes, players are not willing to confront whatever it is that ails them and they prefer to dissociate by distracting themselves in different ways. Mindfulness-acceptance-based approaches might highlight the value of defusion—learning to step back from your thoughts without over-identifying with them. That has its place. But in my experience, some athletes sense there’s something unresolved underneath the thought—and simply letting it pass doesn’t feel like enough. That’s where decatastrophizing comes in: it helps them unpack and challenge the root assumptions driving the anxiety.

Athletes know that there is some problem there, something that is causing this anxiety or tension, and continually refocusing to the present moment isn’t giving the promised relief. But that’s a conversation for another day.

With So what if thinking, the idea is to show the individual that their anxiety is usually caused by catastrophizing the perceived consequences of losing, or not defending their ranking points, or whatever it is that might be bothering their performance on the court. When done well, this process of decatastrophizing helps athletes see that their fears often hinge on imagined consequences that are rarely as devastating as they initially seem.

In this way, we encourage players to start thinking about their coping skills and strategies and also ask them to reflect on their rescue factors: these are the personal, social, or psychological resources an athlete can draw on to recover from failure or from adversity.

Try It Out Yourself

If you feel you’re ready to try and confront the thought patterns that might be causing you excessive anxiety and tension, I encourage you to try out the following activity.

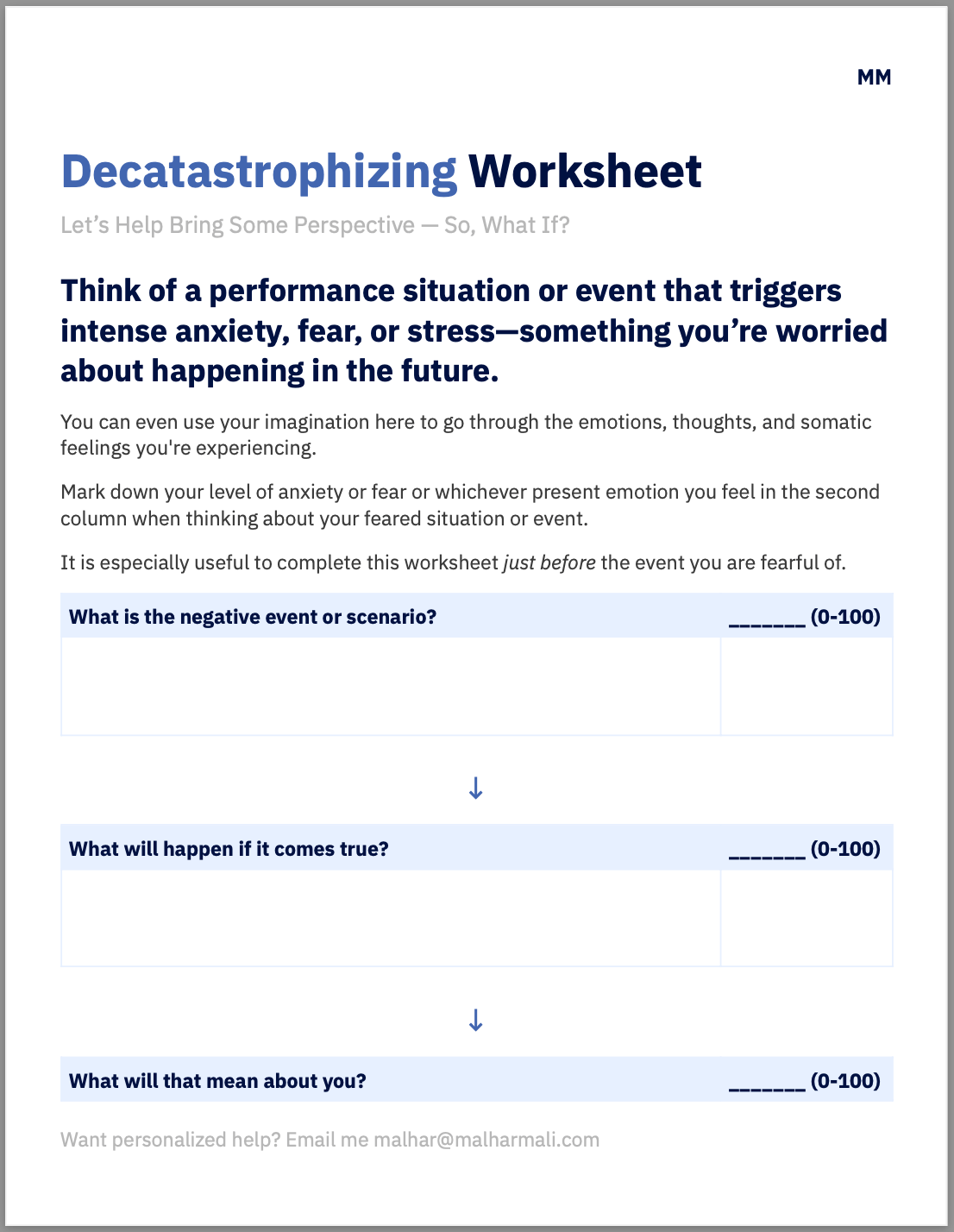

And because I love giving away stuff to you for no cost, I’ve made a Decatastrophizing Worksheet for you to download—free of charge. Here’s a preview:

And you can download it below:

I also want you to also note the level the level of anxiety that you have as you go through the sheet and fill it out.

If you’re still with me, I hope you’ve realized that the goal of an exercise like this is to get you, the athlete, to think that what you’re imagining could happen in terms of worst-case scenarios, is often distorted and catastrophized in many ways.

As is the case many times, our worst-case scenarios never even come true. Our fear of losing or of not getting those ranking points or whatever it might is often more intense than the actual event itself.

Sure, it might hurt to not achieve our outcome goal. But is it as bad as our minds are making it? Or is there more to the picture.

Finally, I will leave you with the full quote from where we began, by the Stoic Seneca, taken from a letter sent to his friend Lucilius, around 64 A.D:

“There are more things likely to frighten us than there are to crush us. We suffer more often in imagination than in reality. What I advise you to do is, not to be unhappy before the crisis comes, since it may be that the dangers before which you paled as if they were threatening you, will never come upon you.”

In other words, our fear is often magnified, and we have a tendency to catastrophize the consequences of our failures.

That is what causes us our anxiety and stress.

P.S.: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy traces its foundational roots back, through Aaron T. Beck and Albert Ellis, all the way to ancient Stoics and Stoicism as a philosophy of life. As an additional note, Stoicism today has been corrupted by “Broicism,” a defiled version of this philosophy that advises young men, amongst other things, to be emotionless, non-reactive, and hardened in their outlook to life and people. This is not what the original Stoics advocated for.

Disclaimer: I am not a licensed psychologist, mental health counselor, PsyD, or clinical PhD. I am currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology and am a sport psychology practitioner-in-training, working toward the Certified Mental Performance Consultant® (CMPC®) credential provided by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP). My work focuses on applied, non-clinical mental performance consulting, using evidence-based techniques grounded in psychology, sport science, and applied sport psychology to help athletes enhance focus, manage pressure, build confidence, and improve performance. I do not provide mental health counseling or clinical therapy. When needed, I will always refer clients to licensed mental health professionals for concerns beyond the scope of performance consulting. I have over 20 years of experience in tennis, including as a player, collegiate and professional coach, and director of programs. I am certified by the Professional Tennis Registry and am a member of Tennis Australia. My goal is to bring athletes the best research-backed insights to support long-term development and performance. If you are a researcher or practitioner and feel I’ve misunderstood or misrepresented any concept, I welcome you to reach out, and I will gladly review and issue corrections if appropriate.